From the beginning of the agile movement, user stories were the primary way to capture functionality. They were written on cards, called story cards. The logic here was that the story cards were meant to be informal, unlike the data flow diagrams that were developed when traditional applications were developed. The idea was that the story cards would be quick to write and could be easily discarded if a particular card was not useful. They were definitely not intended to capture system requirements. In an agile development project, there is no requirements document. The requirements are captured in the executable code that is being developed. Developers take a story card and use that to interview the appropriate users to determine how the story should be implemented. They then implement it. This is true in all of the variants of agile development, including Scrum and eXtreme programming.

Almost everyone on the team ends up writing some user stories over the life of the project. Theoretically, an agile estimator only has to be able to read these stories. However, most estimators also share another project role like product owner. In any case, it is the collection of user stories that forms the basis for any estimating that will be done.

In 2004, Mike Cohn wrote User Stories Applied: For Agile Software Development. Many people consider this to be the most authoritative source of instruction on the development of user stories. He has followed this up with courses on the same subject. The information can also be found embedded in his course for agile product owners.

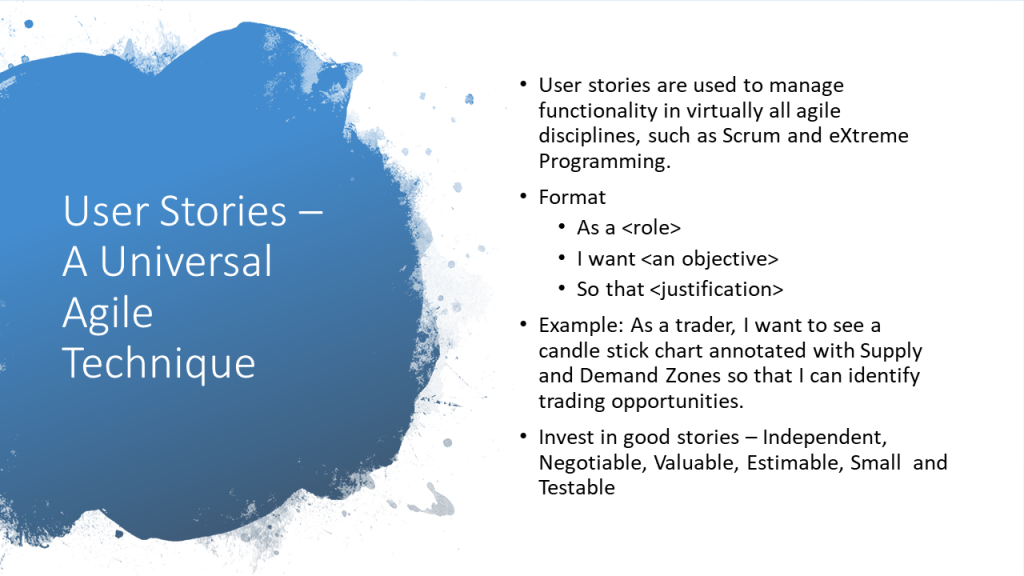

Over time, the format of user stories has evolved to be: As a <role>, I want <an objective> so that <justification>. Role is the type of user that the story pertains to. WordPress has administrators, editors, authors, contributors and subscribers. Each type of user has different capabilities. Administrators can update the WordPress site. They will have user stories related to this. An objective would be a goal. For example, in WordPress there might be an objective to add a new post to the site. The justification is a reason that the objective is being performed. So, an example user story might be “As a contributor, I want to be able to add a new post so that people will see it when they are on the site.”

An example would be “As a trader, I want to see a candle stick chart annotated with Supply and Demand Zones so that I can identify trading opportunities.” A trader would be a type of user. There might be special cases of trader like equity trader or futures trader. Users would know what a candle stick chart and Supply and Demand Zones were. An estimator would have to speculate what would be involved in implementing this. This is unavoidable. In agile development, the user stories are meant to spark a discussion between the developers and the users. By the time the developers understand the requirements, they are already working on the implementation. It is too late to benefit from a better estimate.

Mike Cohn’s book included Bill Wake’s INVEST criteria to evaluate the goodness of user stories. Anyone writing user stories should be familiar with this. Even people who only need to read that should understand these criteria so that they have an idea of the caliber of user stories that they are working with. According to Wake, user stories should be independent, negotiable, valuable, estimable, small and testable.

If user stories are being read and evaluated, the criteria stands on its own. However, when using these as guidance to writing stories, there is a continuing balancing act to utilize these criteria. For example, stories should be independent. A story like “As a trader, I want to see data so that I can identify trading opportunities” is certainly independent. Unfortunately, this violates the criteria that the user story should be small. That makes sense. This latter user story is an epic story that does not really provide enough granularity for planning or estimating the release of an application. Balancing these trade-offs is a matter of design.

User Stories are Independent

In a perfect world, the user stories can be implemented in any order. Are applications developed in a perfect world? Of course, not. Nevertheless, this is one of the criteria that should be aspired to. It is best not to break user stories into programming steps. The example story should not be broken into a series of sequential stories like one to get data, another to analyze it and a third to display it. This would encourage you to implement them in that order.

Independence often has to be balanced with the principle that a user story should be small. A story like “As an equity trader, I want to see any pertinent data so that I can identify trading opportunities” is certainly independent, but it is too large. It is an epic story that will be impossible to estimate or manage.

User Stories are Negotiable

User stories can often be implemented in a several ways. There may be a hamburger version, a sirloin version or a Chateaubriand version. They will take different amounts of effort to implement. Using the example above, it would be good to develop an application where prices were plotted in a candle stick chart and the Supply and Demand zones were developed by the computer. When this was explored, it would be found that different people identify the zones in different ways. Accommodating these different approaches might be the Chateaubriand version. Choosing one approach that everyone could live with might be the sirloin steak version. Displaying the prices on a candle stick chart and making the user identify the zones would be the hamburger version.

Negotiating functionality is an important part of agile development. The first release of an application should occur as soon as possible. However, it has to be of value. Lean marketing practitioners refer to this as the Minimum Viable Product (MVP). Once the MVP is implemented, then customers can get experience with it and direct its future development. Of course, care must be taken not to negotiate away so much functionality that the resulting application is not of interest to anyone.

User Stories are Valuable

User stories must be valuable to either the user or the customer. Users are the people who will use the system. Customers are the people who will pay for it. Sometimes, the users and customers are the same people. Other times, they are different and their needs may be different. For example, a web site might need have the capability to track how users are interacting with it. Users might not need this or ever want it. A customer might want this in order to evaluate the way the site is being used.

User Stories are Estimable

User stories must be capable of being estimated. In traditional agile estimating, this means that it can be compared to other stories to estimate how long it will take, relatively speaking. For example, if there is one story that has already been assigned 4 story points and this story is looks like it will take twice as long, then it will be estimated as 8 story points. When using semi-classical estimating, this means that the estimator can make a reasonable guess regarding the sub-stories that will make up the story. For example, the user story “As a Customer Service Representative, I want to be able to change a customer’s address so that the customer’s contact information is correct” would require an External Input (EI). It would also require an External Inquiry (EQ) because it is assumed that the CSR would be able to see the current address. Finally, there must be an internal logical file (ILF) with customer information to change.

Obviously, being estimable is related to the idea of a user story being negotiable. In the “hamburger” version of the example user story, it might be assumed that the story can be implemented as a single External Output (EO) that accesses a single logical file. The “sirloin” version might need to access more data. At the very least, if might call for more complicated algorithms. The “Chateaubriand” version would probably require several data sources and some type of capability to maintain the various definitions of Supply and Demand zones.

User Stories are Small

Smallness refers to the effort required to implement a user story. User stories get assigned to iterations and releases. If they are large, it is difficult to assign it to an iteration. In a perfect world, the stories would all be small and independent. If there was some excess system development capacity in an iteration, the next small user story could be put in. In reality, user stories have different sizes and some can take up a significant amount of an iteration.

It was already mentioned that user stories being small and being independent are often at odds. One attribute cannot be abandoned for the other. It is an exercise in design to find the appropriate balance. There is a similar issue regarding being small and being testable. A user story that asks for a report to be displayed can be shown to be correct by checking the report. A smaller story that simply requires data to be read still needs to be tested to verify that the data has been read properly. This may call for software to be written simply to display the result of the read. That software has no benefit to the user in the working system. Nevertheless, some amount of test scaffolding is part of most applications.

User Stories are Testable

One of the principles of project management is that there needs to be a way to unequivocally know that a task is done. This is the same for a user story. There must also be a way to validate that it is done correctly. Test cases have always been a part of software development. With iterative development and multiple releases, it is critical to be able to continually verify that the application is functioning properly.